“There’s bitter, which is decidedly distasteful, right? And there’s sweet. Bittersweet is that combination. In the film, all these things come from a girl who’s 19 years old, and it is that—bittersweet, like a pain you desire. It’s a contradiction. It’s the past, and it’s probably not good for me, but I like it. I feel comfortable in it. It’s like an ailment that you enjoy.”

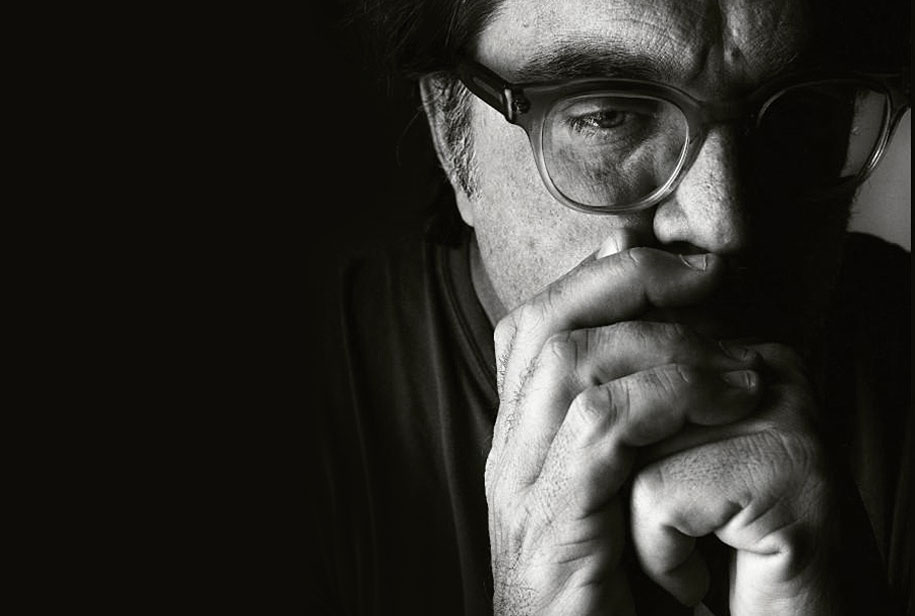

MARK PELLINGTON

After graduating from the University of Virginia in 1984 with a degree in rhetoric, Mark Pellington began his career working at MTV as a promo producer and freelance music video director. In 1992, his video for Pearl Jam’s “Jeremy” earned him Best Director at the Billboard Video Music Awards, and in 1993 it picked up four MTV Video Music Awards, including Best Director and Video of the Year.

Today, Mark Pellington is a music video, film, documentary, and television director. His videos for U2, Pearl Jam, Michael Jackson, Linkin Park, Foo Fighters, Bruce Springsteen, Nine Inch Nails, Alice in Chains, The Dave Matthews Band, Demi Lovato, The Fray, Jason Mraz, Cage The Elephant, and Kid Rock, among many others, have earned him international recognition as one of the world’s premiere music video directors.

Last year, Pellington’s feature film The Last Word (Shirley MacLaine and Amanda Seyfried) considered the consequences of an overly-shaped life. His latest film, Nostalgia, explores our relationships to the objects, artifacts, and memories that shape our lives.

We spoke with Mark Pellington by phone about his upcoming film, his career as a director, and how he defines nostalgia.

Hannah: You helped develop the story for your new movie, Nostalgia, before you directed it. How is the experience of directing something you wrote the story for different than that of directing something completely written by someone else?

Mark Pellington: You know, when you’re directing material that you developed and contributed to the writing of, you’re more personally committed to it … I’m emotionally or personally committed to the scenes and the idea. Sometimes when I’m directing a genre piece, that is, let’s say, a non-dramatic or emotional scene, then I can kind of change my temperature and become kind of just a shooter. I guess the answer is that it really depends on the genre of the movie, because if it doesn’t really have layers of emotional depth, you access a different part of your brain to direct it. Either way, you’ve got to be really focused.

Cailin: That makes sense. I imagine it would be easier for you to really tap into the emotional aspect of a story that you wrote, because you know where you’re coming from personally.

MP: Well, yes and no. Sometimes you could be too close to the material. You know, sometimes a certain degree of objectivity actually helps. Each situation is different. Sometimes the actor’s really personally connected to it. Sometimes that’s really good, and sometimes you want to kind of come at it from a different place. Just ‘cause you’re personally connected to something doesn’t mean it’s good.

C: You’re well-known for directing high-profile music videos as well as short films, feature films, documentaries and TV shows. You’ve kind of been all across the board. As a director, how do you decide when you want to work on each type of project? Do you have a long-term plan, or is there some kind of formula to it?

MP: There’s no plan, and there’s no real formula, to be honest with you. I started doing music videos and commercials, and even as I expanded into doing movies and TV, I never gave up my love of music and music videos. I loved the abstraction in them, and loved the ability to kind of explore visually things that could be not so much about plot, but could be very personal. I explore a lot of very, very deeply personal things in my music videos, and thank God I have the songs of the artists who allow me to put those in there. I’m shooting one this weekend for Imagine Dragons, it’s like this very ambitious short film/musical film … A lot of the scenes and the ideas are very personal to me as well as to the band. I tend to shift gears right when I’m done filming something that’s very emotional, like Nostalgia. I’m gonna go do a pilot for NBC that’s a big action, kind of conspiracy thriller. It’s nice to shift gears—I wouldn’t want to keep making only sad, dark movies. I’m lucky enough that I kind of gravitate from one to the other. Unconsciously, after doing a lot of plot stuff with actors, you want to go be a little more free-form and abstract: short, weird, arty things. Then, those don’t pay the bills, and I’m like, Oh, I’ve got to go pay the bills, do some commercials. But you can’t always control what comes in.

C: You were talking about working with artists to make music videos. As a director, what is the process like of collaborating with an artist? Like, do you go to them and say, “You know, I’m doing this video for you, this is the idea I have in mind, what do you want to add to that or change?” When it’s that collaborative, when you’re dealing with someone’s personal music—maybe the lyrics are personal to them—do you go to them first and say “This is what I want to do” and go from there?

H: Or do they come to you?

C: I’ve just always wondered how that works.

MP: You know, each one’s different. I have approached certain artists and said, “I really want to work with you.” For example, Cage the Elephant—I always wanted to work with Cage the Elephant, and knew their management. They said, “Great! Well, here’s the album, here’s the first two singles.” Usually, it’s based on singles. And I say, “God, I really like this song Cigarette Daydreams”, and they’re like, “Oh, we’ll never make a video for that.” Four months later, they’re like, “You know what, people really like that song. We’re thinking about doing a video.” So I then talked on the phone with Matt Shultz, and we concocted a story, and his wife was the actress in it, and then I write the treatment and they leave me alone. So usually the artist will approach me, or my representative will find out about a song and I’m like, “Oh, I love them, let me hear the track.” And If I like the track, I like to write ideas … You talk to the artist. Sometimes they have a vague idea and your job is to flesh it out. That’s what happened with Demi [Lovato] “Tell Me You Love Me”—she wanted to be a bride, and she wanted to be left at the altar. That was pretty much it. An argument, what the argument’s about—that was my idea. Then it was her idea [to cast] Jesse Williams. She used her clout to go get him to be in. So, she in a way is really like a producer at that point. Generating the material, securing the talent, she’s really driving the vision. Sometimes the bands are like, “Great, do whatever you want to do. We like your work, we trust you.” It’s usually about trust. You can smell those things—if they’re fearful, then they should hire someone else, you know?

H & C: Right.

H: Even when you’re working with an artist who has lyrics that are important to them, or an actor who has scenes that are important to them personally, is there a common thread that ties all of your projects together? Like, what is it about your work that would make somebody say, “I can tell Mark Pellington is behind this”?

M: That’s funny, I have people tell me that, that they can see something. Certainly in music videos over the years—kind of a certain editing style or certain way a shot looks or feels. Certain lenses or lighting schemes. But if you’re doing a music video or commercial or movie it kind of changes. I’m always surprised, even if I do a comedy/drama, like with Shirley MacLaine [The Last Word], somebody could say, “Yeah, that felt like your movie.” You know? Like, Okay, that was interesting.

H: That was a great movie, by the way.

MP: Thanks. Here’s a really interesting way that you know. I did a movie about seven years ago, a sweet movie with Luke Wilson called Henry Poole is Here, right? About a guy looking for hope in a hopeless world. It was kind of a spiritual fable, really heartfelt, it had a lot of music and stuff. Somebody online—I don’t know where these people get the time to do this—they cut like a horror/thriller trailer with the footage from the movie. And oh my God, it looked like one of my other movies! It just goes to show the power of music and the power of editing to kind of manipulate and change the intention, so the audience can perceive it a certain way.

H: How do you think the actors you’ve worked with over the years would describe you as a director?

MP: I would probably say pretty passionate, pretty open-minded. I’m not very controlling. If you love the text of the script and you love the actors, you really have to let them do their thing. We need to be directors, they need to be guided. But the same way that the people that hire you to direct it need to trust you, I feel that way about actors. When you do commercials with untrained actors, you really have to forcefully get the performance out of them in a way that you don’t have to with Jeff Bridges or Shirley MacLaine. But even then, all actors want to be directed, some just need to be directed or guided more than others. But the older I get, the more I want to be surprised.

H: Let’s talk more about Nostalgia. The synopsis says that the movie explores the relationship to the objects, artifacts, and memories that shape our lives. I think that is so intriguing because so often we’re told that the physical objects in our lives don’t matter. What would you say to that?

MP: I feel the complete opposite. The movie explores for someone age 19 to age 80 what an object means. And what you hold in your hands versus what you hold in your heart. What is on your shelf or in your brain, a memory of someone, a photograph, a remnant of the life you lived or shared with them versus something that’s intangible. The movie is five different stories which explores all those ideas. It kind of crosses generations without becoming a treatise on technology, or why analog was so much better than digital. It explores those things through both the other characters and the objects. You’d be able to kind of find your worldview in the movie.

C: I guess the point then is that, you know, people say not to be materialistic and that objects don’t matter, and your movie is saying that objects aren’t just objects…

H: They are made personal by people.

C: And think about all the objects we attach meaning to throughout our lives.

MP: Your mother has given you something in your life that means something to you, right?

C: Right.

MP: Because it’s your mother. You have an emotional relationship to that object. Say you went on a trip—you have memories from that. Your identity is based on your experiences. An accumulation of all your life experiences is your identity. And sometimes there’s a physical reminder.

H: Mmm-hmm.

MP: Why don’t you throw away that sweater? It’s eight years old! “Because I love it.” What about those shoes? “I bought those shoes in Florence over summer vacation. I love them.” I mean, you don’t need forty pairs of shoes, do you?

C: [laughs] Nooo.

MP: What do you need emotionally? What do you need physically? It changes the older you get. There’s minimalists and there’s hoarders, and each person can kind of find themselves within the spectrum. Materialism is, Oh, I need a bunch of things around me because I feel hollow in my life, and if I have shiny, new objects, it fills my life. Well, those shiny new objects are no different than another person’s alcohol, another person’s addictions. There’s addictions to objects. There’s holding onto something from my grandfather that reminds me of him every time. Well, I don’t want to forget about my grandfather! My grandfather meant something to me. You know? That’s kind of what the movie’s about. It asks a lot of questions and lets you find yourself within the answers.

C: How do you define nostalgia?

MP: Nostalgia is a longing for something other than the present. It’s an emotional connection and a desire to be in a place other than a place you’re in now, which is often the past. The term nostalgia means “a longing for home.” It was originally coined as a phrase by psychiatrists in Switzerland in the 1600s. The soldiers would come home with PTSD— traumatized—and they would be longing for home. They just want to go home to a comfortable place. It’s an illness.

C: Would you say the feeling—some call it bittersweet—is more bitter or sweet?

MP: Well, there’s three words. There’s bitter, which is decidedly distasteful, right? And there’s sweet. Bittersweet is that combination. In the film, all these things come from a girl who’s 19 years old, and it is that—bittersweet, like a pain you desire. It’s a contradiction. It’s the past, and it’s probably not good for me, but I like it. I feel comfortable in it. It’s like an ailment that you enjoy.

C: A lot of people say that we look back on our past with rose-colored glasses, that we remember past times as being somehow better than they actually were. Do you believe it’s in our nature to do that?

MP: I think that’s actually what nostalgia is. That somehow, it was better before. Somehow, what I had before was better, and that dissatisfaction with the present is what fuels your revisionist’s vision of the past, right? So, I’m changing my view of the past because it suits my purposes because I’m dissatisfied with the present. Like, “Wasn’t sixth grade a lot better than eighth grade? Eighth grade kind of sucks! It was so much easier before.” Then you’re in eleventh grade and you’re like, “God, I liked eighth grade a lot better. Eleventh grade sucks!”

H & C: [both laugh] Yeah.

MP: And then you’re in college and you’re like, “High school was so much better!” So, at any one point—because you’re always striving to go ahead—the most difficult thing is to be where you are and be cool with it. “I will enjoy this right now.” I think this is what most people do. You enjoy your time with your friends, you enjoy the movie, but you’re kind of always like, “Well, what’s gonna happen next week?” Because you have desires, and goals, and dreams. So part of that changes as you get older. You’ve lived enough life and you look back and you’re like, “You know, that was pretty good. I feel pretty proud about that.” Or, “Ahh, I’m never going to get to do this.” Or, “I’m never going to get to have that experience.” So, again, on the spectrum of life, there’s regret and there’s ambition. So the rose-colored glasses come from that. You know, It was better then, wasn’t it?

C: What do you think is our relationship with memories? Whether they’re good or bad, once they’re in our past, how do these memories influence us as we move forward in life?”

MP: Memories are our recognition and our acknowledgement of our experiences … I mean, I’m 55 and I cherish my memories, and also cherish my ability to remember them. I mean, my father died. He had Alzheimer’s and didn’t remember anything! He didn’t remember who I was! Memories are a component of your identity. If you can’t remember anything you did, then, did you exist? Do you even exist if you can’t remember anything that happened? And that’s—you know, that would be brutal! But boy, if you remember, like, “That was fun”…it’s good because all these things tie together. Everything’s tied together. Nostalgia’s memory, and it’s all that stuff, all those feelings. In the movie Catherine Keener played John Hamm’s sister, right? And they’re going to the house where they grew up. Their parents have moved and left a lot of shit for them to go through. And she’s trying to give away some of the stuff to her daughter who’s going to college. And she’s like, “I don’t want any of this stuff! I don’t need any of this stuff. This stuff doesn’t mean anything to me, it means something to you.” And Catherine Keener’s like, “Oh my God, but boy, do you remember how easy it was to sneak out?” So in a way, she’s remembering being 17 but she’s dealing with her 18 year old daughter who’s from a different generation. They see records in the attic and they’re like, “Oh, what are these? Can’t I just download the music?” And it’s like, “No, it’s not about downloading the music. You can listen to the music, but it’s different than listening to vinyl. Each character looks at it differently. The movie’s very intense and there’s sad parts to it, but it also has a lot of ideas for you to chew on.

H: Last one for you, Mark. What time in your life do you feel most nostalgic for?

MP: [sighs] That is a great question. That is the best question I’ve ever been asked. That’s really weird.

H & C: [both laugh]

H: We’re doing something right, then!

MP: Because it’s so…like, in a way, to be really honest with you, [through] all the videos I’ve done, and all the movies, in the last few years I’ve been healing from grief from losing my wife when she was young. [She’s] the mother of my daughter, who is almost 16, she was two then. And so, on one level I’d want to say I’m nostalgic for the time I was married, but I’m actually not. I’m nostalgic for what’s going to happen in the future. Because the whole point of making this movie was for me to be able to live more in the present, and not live in the past. I don’t want to live in the past. I’ve been living in the past for a long time, so I want to just kind of be here now and look forward.

C: You’ve learned something from your own filmmaking experience!

M: Frankly, yes. Every film and every music video is kind of made for a reason, and I could never make this again, the same way I could never make the same movie I made five years ago again. You could never write a diary entry the same as it was three years ago.You’re not the same person. All your experiences influence who you are and your worldview. What you used to think was stupid, you think is cool now. What you used to think is important isn’t important anymore. So you change what you want to say, how you want to say it changes, and at the end of the day you put behind your body of work as an artist, a writer, a filmmaker, a designer, a stylist, whatever it is, and you say, “Yeah, I made some cool stuff, I made some stuff that made people feel and contributed something to the world.” You know? And that’s up to every individual to determine why they’re here. Why are we all here? And some people, their job is to raise a family, and they’re a nurse, or they work as an insurance guy…and you know what? I think everyone’s purpose is defined by something larger than us.

Nostalgia will be released February 16th, 2018. You can find Mark Pellington online at markpellington.com.