As the second anniversary of the tragic Bucks County, Pennsylvania murders of Dean A. Finocchiaro, Thomas C. Meo, Jimi T. Patrick, and Mark R. Sturgis approaches, members of the community reflect on how they were affected by the crimes perpetrated by locals Cosmo DiNardo and Sean Kratz, and the upcoming true-crime special on the case

During the first week of July, 2017, there is a shift in energy in our hometown of New Hope, Pennsylvania.

The typical Bucks County summer of towpath walks, window-shopping in quaint local shops, and bustling town streets is at first only briefly disturbed when one one young man, Jimi T. Patrick, age 19, is declared missing. Strange for a place like New Hope, sure, and if you hear about it, you raise an eyebrow – but there is a world of explanations, most with uneventful endings – and life goes on.

Elsewhere in the northeast United States, locals are up in arms after Governor Chris Christie is seen with his family enjoying his 4th of July weekend on a New Jersey beach that is closed off to the public during the government shutdown. At the same time, the world is debating whether a newly-recovered photo from the National Archives suggests that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan may have survived their final flight. New Hope residents are still spending their days jogging alongside the Delaware, posing for photos on the bridge that connects Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and going home to their families as the sun sets.

Two days pass with no sign of Patrick. Then questions turn to concern when on July 7th, three more locals disappear. All between the ages of 19-21. All male. All gone at once.

That second weekend of July, 2017, no corner of New Hope seems entirely safe.

Parents hold their children indoors. Helicopters roar over residential neighborhoods, passing over the same areas again and again and again. At 20 years old, we are warned by our mother to not go out alone, and to skip our neighborhood walks. When we do step out, we are stopped by strangers who ask us to “be careful.” Just up the street, as the first Friday Night Fireworks of the season lights up the sky over the river, all four missing men, Patrick, Dean A. Finocchiaro, Thomas C. Meo, and Mark R. Sturgis, are already dead in a shallow grave, shot, burned, and buried with a backhoe. Their murderers are Bucks County locals Sean Kratz and Cosmo DiNardo.

A Troubled Teen

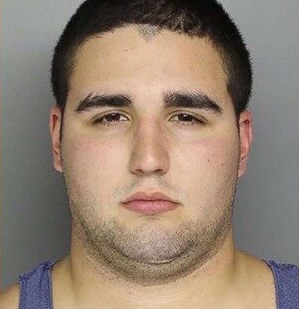

In August of 2011, Cosmo DiNardo has his first run in with the law. The complaint? DiNardo, then a young teenager, is illegally riding his ATV on the street. By July 12th, 2016, 19-year-old DiNardo, a member of the Bensalem Drug and Alcohol Advisory Board, has racked up 23 police encounters. It is on that day that Sandra DiNardo involuntarily commits her son for mental health concerns. He is evaluated by Lenape Valley Crisis Center before going to Doylestown Hospital, where he is held for an unknown length of time.

Between mid-October and November 2016, DiNardo is banned from the campus of both Holy Ghost Prep (where he graduated high school in 2015) and Arcadia University (where he was a student for one semester). He shows up to the Holy Ghost Prep open house loud, disorderly and uninvited, and is escorted out before being banned from campus. The very next month, DiNardo is banned from Arcadia following several “uncomfortable” verbal interactions with students when he went to re-enroll.

“He asked out my roommate over Facebook messenger once after she posted in the Arcadia 2019 Facebook group,” says a student in Cosmo DiNardo’s graduating class before he dropped out, who asks to remain anonymous. “He said some sort of generic, ‘Hey you’re hot, you should go out with me.’ He frequently posted in the group, telling girls they were hot then leaving his number.”

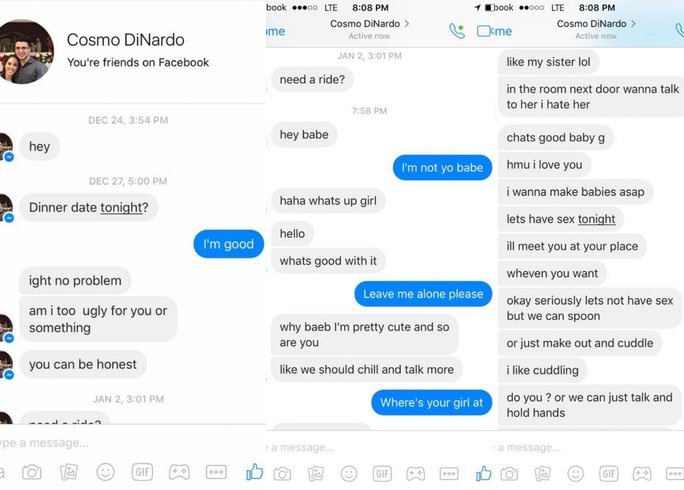

After the story breaks, another woman, Ashley Lauren Mancini, who was also connected with DiNardo via Facebook before the murders, posts screenshots of DiNardo repeatedly messaging her with sexual advances. When asked for further comment by Philly Voice, Mancini declines to comment further on the messages, but does indicate that they were sent in January of 2017.

That month, DiNardo sits in a college classroom for the last time, taking a one-credit class at Bucks County Community College.

Then, things start going downhill.

Up In Arms

On February 9th, 2017 Bensalem police arrest DiNardo for the possession of a 20-gauge Savage Arms shotgun, which is illegal for him to own because of his involuntary commitment the year before. He is arraigned, then released.

In May, DiNardo gets into a one-person ATV accident at his family’s farm on Lower York Road. He reports a broken ankle and is taken to an unspecified hospital.

In the middle of DiNardo’s preliminary hearing on the gun charge, which is held from March 1st to May 30th, 2017 after being continued several times, DiNardo rear-ends Bensalem resident Adam Moore. The gun charge is dismissed, but Moore sues DiNardo over the car accident.

The First Man Disappears

Friends and acquaintances of DiNardo’s say that in the weeks before the murders, DiNardo brags about having someone killed over a debt and makes “scary insinuations.”

It is around this time that Margery Rutbell, who lives on Upper Mountain Rd. near the DiNardo family farm, notices something unusual as she walks her dog.

“I was surprised and curious to see at least two late-model cars parked on the field that is bordered by Upper Mountain Rd. and Rt. 202,” says Rutbell. She calls the Solebury Township Police to notify them of the sighting, but is never told whether they followed up on her tip.

“You simply do not see modern cars in apparently good shape tucked in between the edge of a farm field and the adjacent shrubbery,” Rutbell adds. “It was pretty clear that they were ‘in hiding.'”

Rutbell suffers from memory loss and cannot confirm when she spotted the cars in relation to the unfolding of the case. She admits that she doesn’t regularly follow the news, and only later began to wonder whether the cars belonged to victims of DiNardo or Kratz – from the infamous case or otherwise.

“My assumption now is that the cars were owned by the victims of DiNardo and Kratz, who probably expected to make money on the sale of those cars. I hope that there were no additional victims of these murderers that the police never connected to DiNardo and Kratz.”

On July 6th, DiNardo’s former Holy Ghost classmate, Jimi Taro Patrick, 19, of Newtown, is reported missing. DiNardo later tells investigators he picked Patrick up to sell him marijuana, requesting that Patrick bring $8000 for a quarter pound.

When Patrick shows up with $800 and 2 ounces of weed, DiNardo suggests selling him a gun instead. As Patrick goes to shoot the 12-gauge shotgun, DiNardo shoots, kills and buries him in a remote part of his family’s 90-acre farm with a backhoe.

“I go, get the backhoe, dig the hole, said a prayer, put him in the hole,” DiNardo says in his confession.

Then he burns Patrick’s money.

“I didn’t want the kid’s $800. I didn’t kill him over the $800. I wasn’t robbing him,” DiNardo says. “This was not going to go good for me. The guy would have shot me if I went to meet up with him and I didn’t have the money.”

On the morning of July 7th, DiNardo buys nearly $300 worth of steaks and fish for his family. He picks up his cousin, Sean Kratz, 20, before delivering the food to their grandmother’s house.

Cousins Kratz and DiNardo are not close. DiNardo later tells investigators that he had only begun hanging out with Kratz a few months prior to the killings. In fact, DiNardo admits during his confession he can’t even remember what last name Kratz used. Perhaps the biggest thing the two have in common is their history of violence: At the time of Finocchiaro’s murder, Kratz is out on bail following a pair of burglaries in Northeast Philadelphia.

When the food is delivered, it’s time for another drug deal.

Another Three Gone

July 7th is the day Mark R. Sturgis, 22, of Pennsburg, Thomas C. Meo, 21, of Plumstead, and Dean A. Finocchiaro, 19, of Middletown, are seen for the last time.

The cousins drive Finocchiaro from Bensalem to the DiNardo farm. There, Finocchiaro unknowingly rides to his death on a four wheeler alongside the cousins, passing Patrick’s freshly-buried body on their way to a wooded area of the property.

Kratz is instructed by DiNardo to shoot Finocchiaro.

“He wanted me to rob [Finocchiaro] and then to shoot him,” Kratz says in his confession tape. “I wanted to go home, but [DiNardo] just made it clear that he wasn’t taking me home.”

When he doesn’t, DiNardo leads him to a barn, where he offers to show Finocchiaro a Vespa. Nervous, Kratz lights a cigarette while Finocchiaro scrolls on his phone.

“[DiNardo] gave me a signal — a hand gesture as a gun,” Kratz says in the confession recording. “I kinda was hesitant. I pulled the gun out. I aimed it in the air, closed my eyes and fired a shot.”

Finocchiaro collapses and dies, then DiNardo shoots the already-dead Finocchiaro a few more times as Kratz runs out of the barn. He vomits with horror, and DiNardo laughs at his cousin, who had never seen a dead body before.

“His head was split the hell open,” DiNardo says during his confession. “Half his brain was in the barn.”

Finocchiaro’s mother is the first to report her son missing — but he is already dead. A previously-planned marijuana drug deal turned into a robbery, and ended in murder.

For local filmmaker Lawrence R. Greenberg, this circumstance — in which men who did not know each other well met in secrecy in the interest in buying drugs — raises questions about whether these crimes could have been prevented had marijuana been legal in Pennsylvania.

“Drugs bring strangers together and have their own culture,” says Greenberg. “The culture around marijuana includes following strangers to secluded areas routinely. I think it would [change with legalization].”

As of late June, 2019, 11 states and the District of Columbia have passed laws legalizing marijuana for recreational use. Pennsylvania is still not on that list.

Bent Out of Shape

Amber Watson Tardiff is a mother of two and neighbor of Dean Finocchiaro at the time of his murder.

“Word spread pretty quick that [Dean] was missing,” Tardiff says. “Initially when he went missing, the parents in the neighborhood were freaked out for their kids because we were worried there was a kidnapper. People didn’t want to let their kids out until more [information] started coming out. Then the teenager across the street who knew him had heard that he was last seen with some friends, and this it was possibly a drug thing. We assumed there was some kind of foul play, but didn’t know exactly what until they started finding the kids.”

While the cousins clean out Finocchiaro’s pockets of anything that might help police identify him, and prepare to lift his body into the pig roaster, DiNardo’s father rolls up the driveway, and then quickly turns around. He is with a woman DiNardo doesn’t recognize.

Kratz later says in his confession that DiNardo is “bent out of shape” about the woman, and swears to kill them both.

“I Can’t Feel My Legs”

Later that day, DiNardo and Kratz fatally shoot Meo and Sturgis during another purported marijuana deal.

Tom Meo is instantly paralyzed after Cosmo DiNardo’s bullet strikes his back. Laying on the gravel driveway of the secluded farm, Meo’s shrill screams fall on deaf ears.

“I can’t feel my legs! I can’t feel my legs!”

Meo’s friend, Mark Sturgis, tries to make an escape, but gets only 20 feet before being sprayed with bullets. Sturgis is down, but Meo is still alive, and screaming. Panicking, DiNardo jumps onto his father’s backhoe and rolls over Meo, killing him instantly.

Silence.

The cousins put the victims in a pig roaster, pour gasoline inside and set it on fire. Their work is done.

Cheesesteaks for the Road

DiNardo and Kratz stop for cheesesteaks before driving back to DiNardo’s house in Bensalem, where they both sleep while the bodies burn in the pig roaster.

“I didn’t eat mine,” DiNardo later tells authorities. “I just did something so gruesome. I didn’t have the appetite.”

The next day, DiNardo and Kratz use a backhoe to dig a common grave for the three men’s remains.

As the Crow Flies

“It happened on my 30th birthday, and my girlfriend had hosted a surprise party at my house, which is, as the crow flies, maybe a quarter mile from the [DiNardo family’s] farm. So we had 70 people all drunk and having a great time, while simultaneously this disgusting dude is over there burying these people in the ground.” —Benjamin Albucker, Lambertville resident and shop owner

Meo’s mother reports her son missing after he doesn’t show up for work.

After the bodies are buried, DiNardo wants a shave and a haircut. DiNardo and Kratz go to Kratz’s uncle’s barber shop. There, they throw the victim’s IDs in a sewer. The two also make a trip to a car wash, and visit Kratz’s mother’s house in Northeast Philadelphia, where DiNardo would later hide the murder weapon. They visit with Kratz’s sister and her new baby, where Kratz later tells officials DiNardo made lewd comments to the young mom.

On July 9th, Sturgis’ parents report him missing, and authorities release images of the four missing men to the public. Investigators find Meo’s car at a home in Solebury Township, and Sturgis’ near Peddler’s Village.

“When it was just the first kid, as sad as it is, it could have been a suicide, he might have run off,” says Kara Seymour, a local journalist who covered the case extensively for the New Jersey/Pennsylvania region of Patch. “There are a lot of cases of missing people, and most of the time they find them. But by the time the pair together went missing, then it was like, something is definitely going on.”

Suspected Foul Play

By July 10th, the case of the missing men, which now involves suspected foul play, makes the national news. It is no longer just a missing persons case: it is a criminal investigation, and what started as terror in Bucks Country is now being tracked by people all over the United States. The community, and the country, are watching as investigators search Antonio and Sandra DiNardo’s farm in Solebury Township.

“It was just terrifying,” says Annetta Cseri, New Hope resident and mother of two. “I don’t usually lock my doors unless I’m sleeping. My house is unlocked, my garage is unlocked, my car is unlocked…but I locked everything up [that week]. I kept my kids inside. At first you think ‘Oh, it’s nothing,’ but once we heard those helicopters, I think that escalated everyone’s response. That stuff doesn’t happen around here.”

Greenberg, who for a few years managed a forensic psychiatry facility in New Jersey, suggests it is that small-town trust that enabled the perpetrators to lure their victims onto the DiNardo family’s property.

“When you meet someone here, the local culture prescribes that you assume they are a good person until you are shown otherwise,” says Greenberg. “I meet people easily and introduce myself … I don’t act this way in other places. DiNardo and Kratz probably took advantage of this openness to entrap their victims.”

Later in the day, Cosmo DiNardo is taken into custody on refiled firearms charges from his case in February. DiNardo is accused of possessing a shotgun and ammunition he isn’t permitted to have because of his recent involuntary stay in a mental health treatment facility. The next day, on July 11th, Cosmo DiNardo is named a “person of interest” by prosecutors in the case of the missing men. However, DiNardo is released after posting bond for his $1 million bail in the firearms case. The search of the DiNardo family farm continues.

Degrees of Separation

The husband of the previously-mentioned Patch local journalist Kara Seymour worked with a man who knew Cosmo DiNardo.

“Before [DiNardo’s] name was in the press, when the police were just beginning to follow up on tips and search his property, my husband’s co-worker was like, ‘I think my friend Cosmo might have something to do with [the murders] … His family has this farm up in Solebury, and he is always asking people to ride ATVs and is super aggressive.’ He was freaked out because DiNardo had invited him over to ride ATVs at the farm like the day before the first guy was killed.”

It isn’t long after DiNardo’s bail that he is back in custody. On July 12th, he is charged with stealing a car belonging to victim Tom Meo. This buys investigators time to find evidence linking DiNardo to the missing men case while he is behind bars and out of the community. He is held on a $5 million bail. On that same day, cadaver dogs find human remains on the farm, and the case is named a homicide investigation. One victim found was Finocchiaro. At least two other people were discovered in the grave, but were not yet identified.

“I remember driving by the farm and seeing a backhoe, and obviously, that’s not a good sign,” says Kara Seymour. “Law enforcement was using the backhoe that belonged to the family — the one that was used [by the perpetrators] to bury the bodies — to now uncover them.”

DiNardo Confesses

On July 13th, as investigators try to identify the other bodies, Cosmo DiNardo’s lawyer says DiNardo confessed to his role in the killings of the four men and pointed authorities to Patrick’s grave, in exchange for a promise that prosecutors would not seek the death penalty. DiNardo also told police his cousin, Sean Kratz, was an accomplice. Kratz is taken into custody in Northeast Philadelphia.

By July 14th, both Cosmo DiNardo and Sean Kratz are charged with their involvement in the slayings, arraigned, and held without bail. DiNardo faces charges in all four of the killings, while Kratz is charged in three cases. Prosecutors also disclose the bodies of all four men have been found.

Cosmo DiNardo pleads guilty to the killings and is sentenced to four consecutive life terms. Sean Kratz still faces trial on charges of helping DiNardo kill and bury three of the four victims.

Sean Kratz and Cosmo DiNardo never speak again.

While being questioned by Bucks County detectives, DiNardo breaks down. Soon, in a moment of distress uncharacteristic of DiNardo, he is sobbing.

“I threw my life away for nothing. All I’ve done is nothing,” he cries. “I ruined people’s families.”

The Lost Boys of Bucks County

Andrew Giorgi is a Language Arts teacher at New Hope-Solebury High School.

“Fortunately for the mental health of the students, [many of them] didn’t know the victims or the perpetrators, because they didn’t go to the school [New Hope-Solebury].” says Giorgi. “We covered the story in class, and the response generally from my students was sort of shock that something like this would happen in their town. But because they didn’t know them, they still felt removed.”

Giorgi’s students are, however, looking forward to watching The Lost Boys Of Bucks County, a true crime TV special airing on Investigation Discovery in 2020.

“They are curious to see how their town will get portrayed. The students are very much part of life on Main Street — whenever they go into town, they see people they know, and adults know them — it’s one of those special places in America. I think they are curious to see how it will be portrayed in the special.

Kara Seymour also plans to watch the special next year, though she has some reservations.

“Because it was a pretty terrifying span of a few weeks, it would be sad for the people living here to see [the case] overly sensationalized,” she says.

For locals, the story of The Lost Boys of Bucks County hits close to home.

“It was something that you couldn’t even make up,” says Seymour. “You couldn’t come up with something more horrifying if you tried.”

Now two years since the four murders that stirred Bucks County, the town hasn’t forgotten Dean A. Finocchiaro, Thomas C. Meo, Jimi T. Patrick, or Mark R. Sturgis; and attempting to forget DiNardo and Kratz won’t undo the havoc they wreaked on our tight-knit community. But in true small-town spirit, families still come home to each other each night, and locals still walk the towpath and take photos on the bridge.

Though a drive past the vast farmlands owned by the DiNardo family calls for a solemn moment of reflection, all is calm.