"I believe that in many ways, it was put in my path so it could find the home that it hasn’t yet found. So it can be enjoyed as Edison would have probably wanted.” — Robert Friedman, The Steinway Hunter

Thomas A. Edison purchased Steinway grand piano serial number 66793 in 1890 and owned it for almost forty years. Decades later, the piano found its way into the hands of Robert Friedman.

Thomas A. Edison purchased Steinway grand piano serial number 66793 in 1890 and owned it for almost forty years. Decades later, the piano found its way into the hands of Robert Friedman.

Before he earned his stripes as The Steinway Hunter — who travels the United States restoring and finding new homes for Steinway & Sons pianos — Robert Friedman was a kid who had no idea he was growing up with a former piano prodigy in the house.

It wasn’t until Friedman’s father passed away when he was 19 that his grandmother let him in on a secret: his father was a gifted pianist who was concertized just before his 13th birthday.

“He was supposed to go on and become a classical artist, and his two agents actually released him from the possibility of doing it for a living because he would not take the music out from in front of him,” Friedman tells us on the phone in early November. “He was a prodigy, but he wouldn’t follow the rules.”

Despite not knowing the extent of his his father's piano talent until after his death, at 17 Friedman shared a serendipitous moment with him when while watching, as if for the first time, as his father's playing lit up the keys of an old piano.

“There were some folks who lived across the street from us whose father passed away and there was a piano for sale. It was a Sohmer upright piano,” Friedman explains, adding that there had not been a piano in his home since his father sold his childhood piano when he was two.

“My mother and I begged him to try the piano, to play the piano. I knew he could play,” Friedman says. Finally, Friedman’s father bought the piano and brought it upstairs in their home, where he began playing Chopin pieces. Friedman stood in awe as he watched his father breathe new life into the instrument.

“I never knew how good he was, my entire life,” Friedman says.

But there was something wrong with the piano. A couple of notes were sticking in the upper end. Friedman, who was taking an architectural blueprint design class at his high school, took the action — the working part — out of the piano, and fixed it.

“I never had any training as far as piano technology, but I understood mechanical design,” Friedman explains. “I never told him I fixed it. When he came home, I watched him do a double take when he saw that the note worked.”

Friedman’s father passed away two years later.

“The first piano I ever bought, I sold to my father,” he says. “I saw how much joy it brought him, and I continued on from there. I started buying and selling used pianos, and repairing them. I made a business out of it.”

That was close to 5,000 pianos ago. Friedman is now in his 50th year as The Steinway Hunter, an anniversary that was marked by the media blitz that came with his discovery of Thomas Edison’s Steinway.

In online reviews of Friedman’s book, The Steinway Hunter, multiple users write that through his career, Friedman has shown how every piano has a story to tell. But the story of Edison’s piano is twofold and could fill a hundred books. It is a Steinway, which means it has the intrinsic value of any piano with a tubular action frame and duplex scales — all things that the Steinway family worked through trials ranging from exhaustion to tuberculosis in the 1800s to invent. Its additional historical folklore is just the cherry on top.

In fact, Friedman explains, the Steinway designs from 1878 are still used to this day. According to Friedman, Edison’s piano, which is from 1890, sounds just like a modern Steinway B.

“The people who play it are amazed that it’s an 1890 piano,” Friedman says.

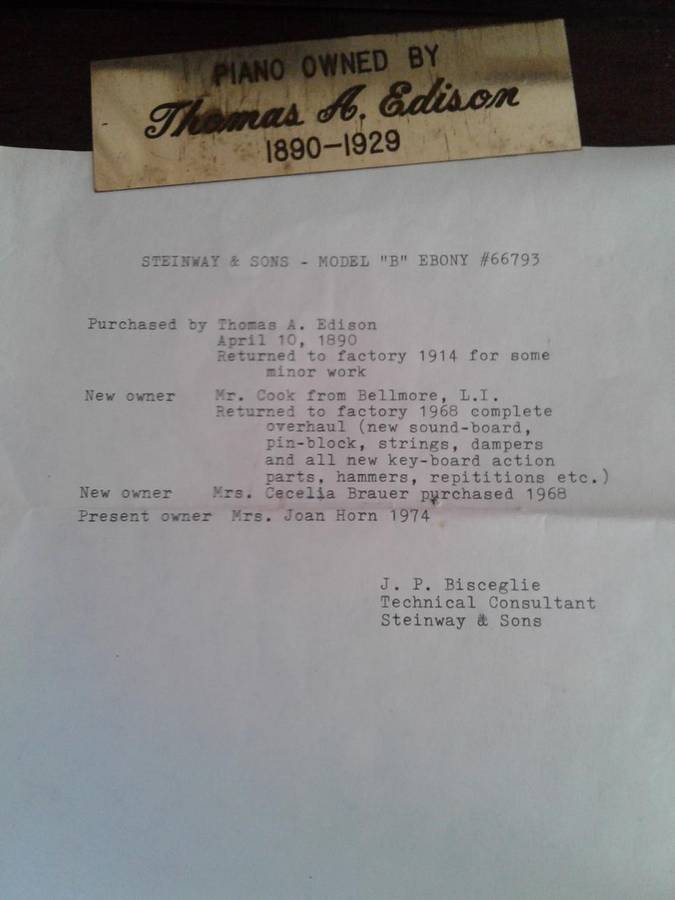

That’s not to say it hasn’t had its share of updates, including a new soundboard, pin block, strings, bridges, and hammer action.

“The one thing they never did — and it’s so good they never did it — is refinish the piano,” Friedman says. “And they didn’t know it had the bite marks on it.”

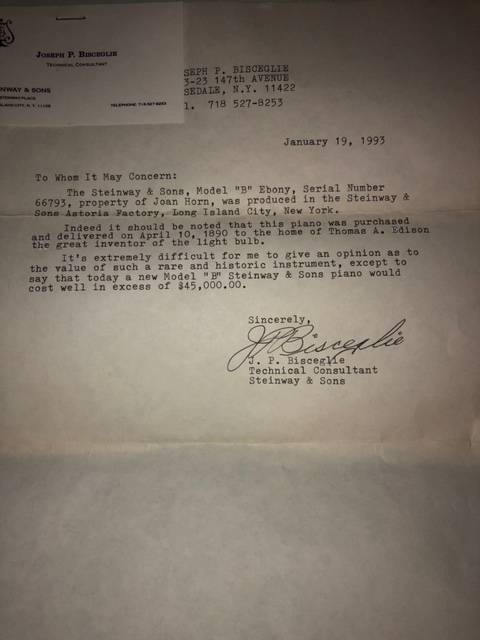

The bite marks, after all, seem to have become the story of the Edison piano, which Friedman bought after it was put up for sale by an estate sale company. Before buying the piano, Friedman needed to confirm that the piano actually belonged to Edison. For that key answer, he poured through documents from Edison’s estate.

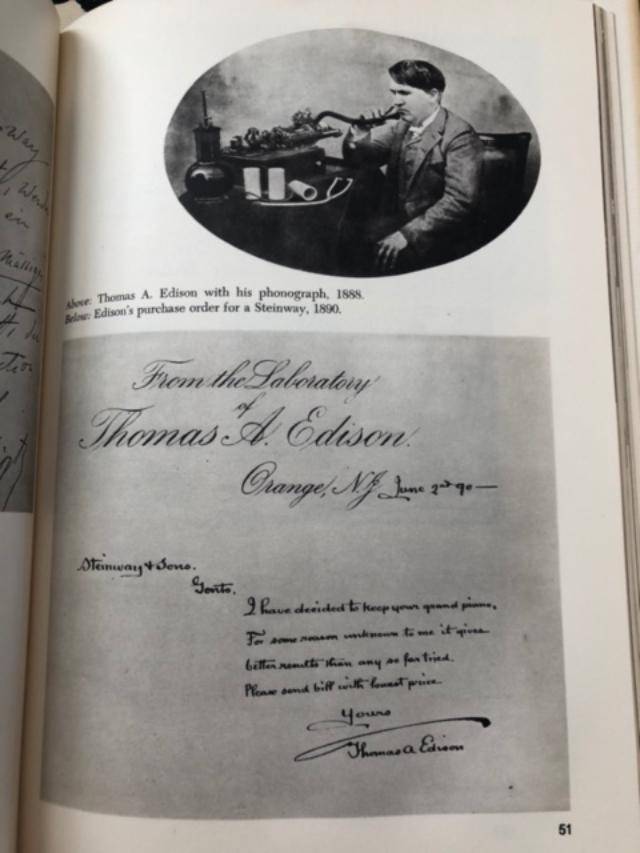

“We matched the serial numbers on the piano to the archives at the Steinway factory and the National Parks Commission, which saved information from the Edison lab in New Jersey,” Friedman explains. “And there was a book which Theodore Steinway wrote, called People and Pianos: A Pictorial History of Steinway & Sons, which included a letter from Thomas Edison to Theodore Steinway that read, ‘For some reason, this piano gives me better results than any other I’ve tried. Kindly send lowest price,’ along with the serial number.’”

Then came the question of the bite marks.

“It traveled hand-to-hand-to-hand and nobody ever mentioned the bite marks,” according to Friedman. “But in the letter to Steinway, Edison said it gave him ‘the best results.’ Well, he wasn’t a piano player, so what was ‘the best result’ he got from it? It’s in all the history books that he bit his piano. Edmund Morris, a Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer, wrote in his book about Edison about him ‘slobbering all over his piano,’ but nobody had the proof.”

“Edison was tortured,” Friedman says. “He couldn’t hear. But he used vibrations to design his recording equipment — his record machines — he bit down, and it was the frequencies from this piano that taught him how to design those machines. The recording industry today might be a little different if it weren’t for this piano.”

So how do you put a price on a piano that might have single-handedly shaped an entire industry?

“I’m more concerned with having it go to where it had to go and then them deciding what they can afford,” Friedman says. “We actually used it as a fundraiser for the Jewish Federation of Ulster County, of which a friend of mind is the president. We had what’s called An Evening With Thomas Edison. He has a big collection of Edison machines; he’s an aficionado himself. He sold tickets and we brought it to his house in Woodstock, New York. We had concert artists, jazz artists, and pop artists come, and it was a big success. In a way, that would be a fun thing — if people just wanted to use [the piano] for that purpose.”

Is there a certain feeling you get, we ask Friedman, while sitting at a piano which belonged to such a prominent figure in history?

“You’re asking, is it exciting or is it spooky?” Friedman asks.

“Both,” we say.

“The piano calls to you to come over and play,” Friedman says. “I have to watch how I make a suggestion about this, but many people knew this piano was for sale, but not many people decided to take it on. I believe that in many ways, it was put in my path so it could find the home that it hasn’t yet found. So it can be enjoyed as Edison would have probably wanted.”

We suggest to Friedman that it sounds like he genuinely cares to whom this piano goes, other than the person who makes the highest offer.

“Yes,” he says. “It should be played. It shouldn’t be put behind a red rope somewhere in a museum. It pays beautifully. It sounds beautiful. I think it should grace a stage somewhere. I’ve had offers — considerable offers — and I’ve turned them down. I’m hoping that with all the press, someone will step up to bat.”

For a few minutes, we muse with Friedman about the differences between a couple of different paths that piano enthusiasts can take. They might play, like Mozart or Beethoven. Or they might buy and sell, like Friedman. Others, still, collect pianos, and would have difficulty parting with one as special as the Edison Steinway.

“I’ve only kept a few real special pianos in my life,” Friedman says. “I don’t keep them. The whole idea is that they have to keep moving. So I don’t really collect. The pianos are my business.”

To this day, Friedman considers his most valued business partner to be the man who started it all for him.

“Ever since I saw my father’s joy when I sold him my first piano, it’s been an unquenchable thirst,” he says. “The money supports the hunt. I can’t stop. I feel like in some way, my father’s been with me in this since he’s been gone. I feel like I have to keep moving. So I do.”