In loving memory of Evelyn Powers, January 8, 1924 - July 30, 2023.

Story originally published November 2016.

In a quaint neighborhood in the coastal Carolina city of Wilmington, just minutes away from the bustle of Wrightsville Beach, the world seems to stand still. The streets stretch in perfectly-straight lines for miles, sandwiched between rows of picturesque little houses donning American flags and windowsill gardens. For years, on our visits to North Carolina to visit our grandparents, we got our neighborhood walk kicks by searching for toads under the streetlights, going net fishing in the pond, and climbing the picket fence which lines the west side of the neighborhood, trying to solve the mystery of what was on the other side. Through stories and quick encounters, we knew something about nearly everyone on our grandparents’ street. We could tell you about the days before the golf course grew into a meadow, and we could give you the names of every dog who could be heard barking in his backyard. We knew where to find the smoothest rocks to paint faces on, and which tree drops the biggest pinecones. This past August, after all those years of summers and Thanksgivings in Wilmington, we showed up for our visit to Grammy Ball and Poppy’s house thinking we had uncovered everything their stomping grounds had to offer. Then we met Evelyn.

One afternoon during our two-week stay, the two of us were sent by Grammy Ball on a mission to find someone who cared for a delivery of some of Grammy’s freshly-baked homemade peach tart. Standing in her kitchen in the light of her oven, Grammy had pondered aloud which of her neighbors might be around to accept the offer — one of the ladies she played bridge with, perhaps, or maybe the young couple with children who had recently moved in. Who else was around? Suddenly, Grammy’s inquisitive expression broke into a grin. “Evelyn!”

Evelyn? All Grammy had said was her name, and my sister and I were intrigued. “Oh my garsh!” she continued. “Girls, you haven’t met my friend Evelyn yet!” Suddenly, it felt like a crime that we hadn’t, like we had been missing out on something and needed to be clued in. We were about to ask, to be briefed on what we were in for, But Grammy Ball clearly wanted us to go see for ourselves. “You have to meet her!” Grammy cried, then gave us Evelyn’s house number. We ran out the door and were on our way in minutes.

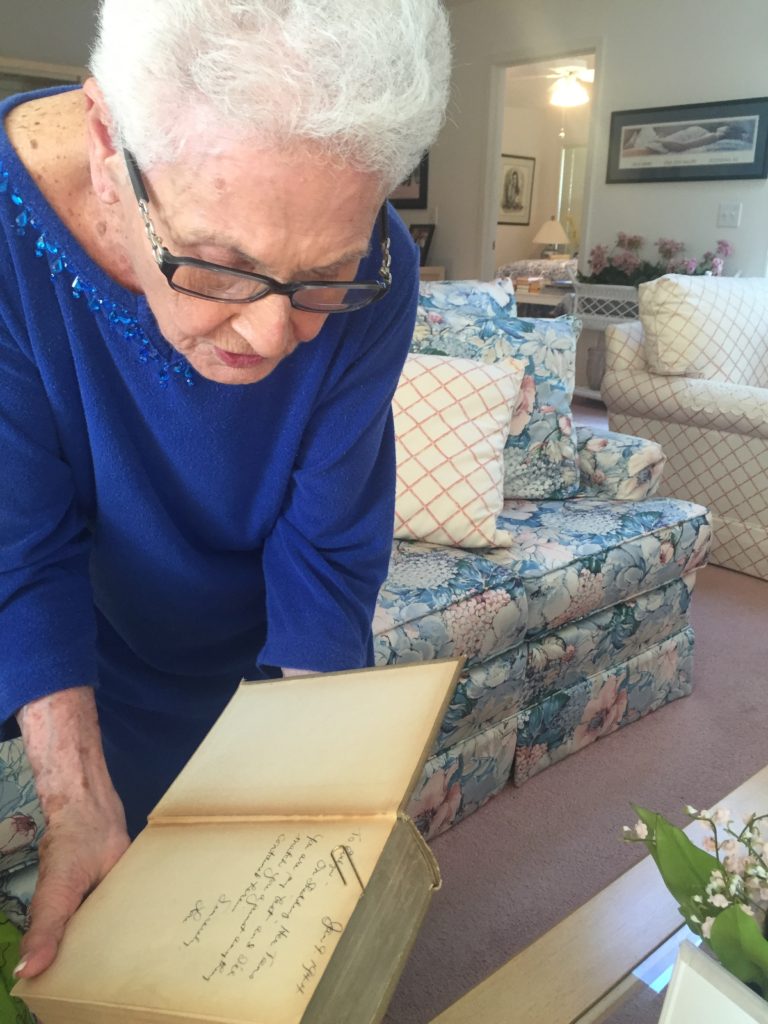

After making the walk through the sunset sky, to the song of bullfrogs and evening cicadas, we arrive on the front porch of a pale yellow house. Within seconds of knocking, the door flies open. There in the entrance stands 93-year-old Evelyn, in a royal blue nightgown, with one of the brightest smiles we've ever seen. She is wearing rose-pink lipstick and pearl earrings, and has a perfect French manicure. We don’t even have time to ask about the peach tart before we are called to her living room and offered a seat on the sofa. Everything from the carpet under our shoes to the shelves of collectibles on the walls is bursting with color.

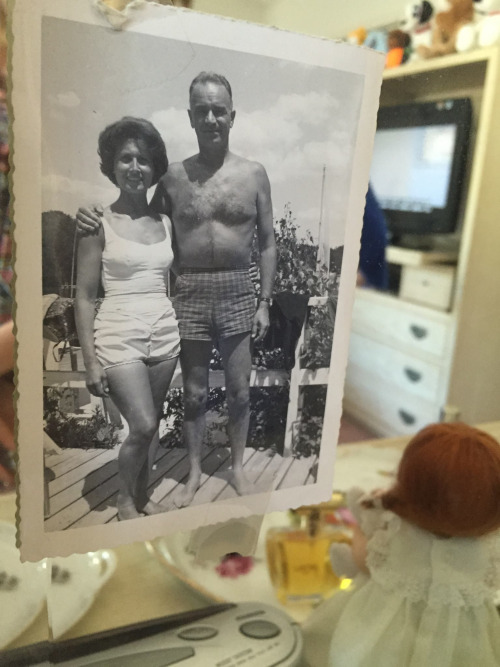

After a quick glance around the room, we each have already found a million things that we want to ask Evelyn about, from a Tweety Bird Pez dispenser to a black and white photo of a young couple standing in bathing suits.

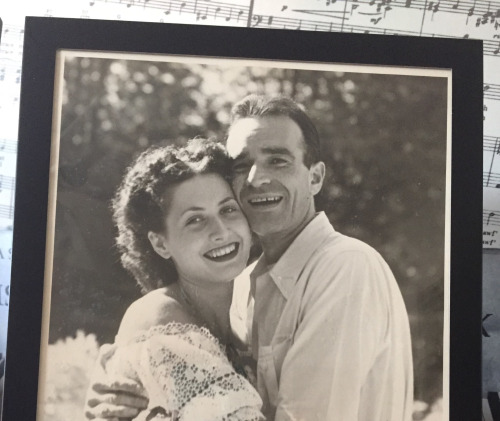

In fact, everything about Evelyn feels like a story that is just begging to be told. So after we are past our small talk, about how we are enjoying our visit with Grammy and how college is going, we decide to turn the tables around on Evelyn. A framed photo of a young Evelyn catches our eyes. Hannah asks her what she remembers from her school years.

We can see in Evelyn’s eyes that the memories are flooding. She pauses, as if to find the words to begin to describe her experience. Then, like she’s backtracking her own memory to give us the backstory, she starts by telling the basics. She was part of the second graduating class of a NYC performing arts high school called The High School of Music & Art, informally known as “Music & Art.” It existed from 1936 until 1984, when it merged into the Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & the Arts.

“Bess Myerson, Miss America 1945, was in my class,” says Evelyn matter-of-factly. “I didn’t know her. I didn’t talk to her. I just saw her around.” She shrugs. She doesn’t say much more about high school. We nod as if to tell her to continue.

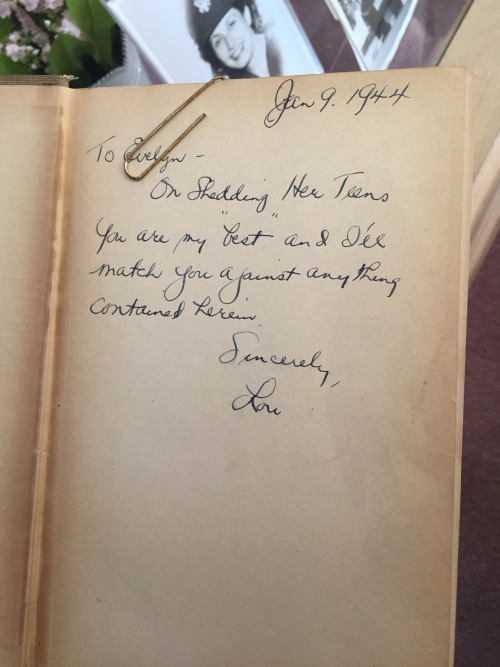

“Then, I went to Brooklyn College. I met a lot of nice girls there. Everybody lived in Brooklyn, and once in awhile I’d stay over at somebody’s house, you know, so I wouldn’t have to go home. We got together a few girls, and had a little sorority. We called ourselves — I can’t believe I remember all this — we called ourselves the Marigolds. The football coach was our housemother. We got very friendly and he gave me a book, but I think my husband George threw it out after he read the inscription. The name of the book was called You Are My Best, and it was excerpts from all famous writers. All he wrote in it was ‘Dear Evelyn, you are my best’ — Look how I remember all this, I adored him — 'And I’ll match you against everything herein.’ And George hated that. I think he threw the book away.”

Evelyn hurries to her feet and begins to sift through her shelves in hopes of finding the book. As she moves around the living room, she continues, “I took some science courses that I was interested in. And because I had taken science courses, I was able to get in the United States Army."

It was around 1940, just after the start of World War II. Evelyn explains that she knew that she had just been given an unlikely stepping stone into the next phase of her life.

"The year that I graduated from college, the Army sent notices around that they needed physical therapists because soldiers were coming back. At that time, the only physical therapist they knew was — What was her name? Sister Kenny! — who was taking care of polio patients. I came home one day and I said to my folks, ‘The Army needs physical therapists and it sounds like an interesting thing to do. Can I go in the Army? And they said, 'Sure, go.'”

Out of context, Evelyn’s initial descriptions of her experiences in the Army sound remarkably like stories from a vacation. Her narration is enthusiastic, almost wistful, and she seems to remember the fond memories before the more difficult ones.

“The Army trained me for a year. And guess where I was trained for a year? At the Greenbrier, White Sulpher Springs, West Virginia. I was there for a year, in that gorgeous, gorgeous hotel, and a place with three golf courses. It was an Army hospital, Ashford General Hospital. I’ve got pictures and things up in the closet."

The Greenbrier, where Evelyn trained, is a luxury resort which was once used as a relocation center for Axis diplomats who had been imprisoned as enemies of the United States. After being seized by the United States Army, the 2,000-bed hospital was renamed Ashford General Hospital, after Army doctor Bailey Ashford. The clinic treated nearly 25,000 patients between its opening in the fall of 1943 and its closing in the summer of 1946. A total of 26 presidents stayed at The Greenbrier during their presidency, the last one being Dwight Eisenhower.

Knowing she had commuted to school during her college years, Hannah asks Evelyn if training was her first time away from home. She laughs.

“No, I went to camp every summer. When I was five years old my mother said I was such a wild Indian, I used to climb straight walls. They had to get rid of me in the summertime.”

Then it’s right back to talking about the Army. "I don’t remember how many girls were training, maybe it was a dozen of us, I’m not quite sure. We lived in little cottages up on a hill. It was very, very nice. Then I got into the Army from there.”

As she looks through her bookshelf in search of photos to accompany her stories, Evelyn stops suddenly when she comes across a book with a gray cloth cover. She takes it in her hands, opens it, and runs her fingers over the pages. She has found the book, You Are My Best. Evelyn grins and motions for us to come over. “Here it is!” she squeals. My husband didn’t throw it out!” As if not to allow herself to be distracted from her story, Evelyn then silently passes us the book and continues talking.

“Anyway, I was stationed in Cleveland of all places. Crile General Hospital. I don’t know how long I was there, maybe a year, and they transferred me. And the rest of my stay was in El Paso. Don’t ask me dates, but I was in about four years.“

It occurs to us that in our twenty-minute look through Evelyn’s eyes into her time as an Army nurse, the conversation hasn’t yet once become even remotely downtrodden. Each narration feels either sentimental or pragmatic. Cailin asks Evelyn if she has any memories of seeing injured patients that have stayed with her. Are there any mental images that she’d like to erase? We get the sense that any pity she had memories of had until that point been overshadowed by earnestness — like her cheerfulness was enough to soften any adversity she might have been faced with. Still, she doesn’t miss a beat.

"I keep seeing one patient all the time in my mind. This poor kid, his legs were in up in the air in splints, and he was so skinny and injured. And he was always flirting with me. I was 22 years old. Whenever I think of going back there I think of this kid.”

Cailin tells her that she often hears stories of people coming out of the Army — whether they are nurses or soldiers — and realizing that they have changed, like what they saw was enough to cause a shift inside of them. She asks if she had that experience coming home.

“Boy, that’s a tough one. I feel like I was still the same person when I got out of the Army. I met a lot of doctors who weren’t very nice guys. You had to be careful."

We suggest, then, that perhaps her experience taught her how to better handle people. Evelyn quickly nods.

“That’s true. A lot of doctors, you know, they were always hitting on the women nurses.” She looks at us. “But otherwise, I had a very nice experience in the Army.”

After coming home, Evelyn went back to New York, where her parents still lived. She began to work at a Veterans hospital in the Bronx. When Evelyn is asked about her homecoming, the conversation quickly turns to her husband, George.

“My grandmother and his mother knew each other from Russia. And I knew George when I was this big [she holds her hand out to her waist]. He lived in Manhattan.” So how, we ask, did they begin dating?

“I got out of the Army and I was home, and my grandmother invited me for dinner.” She laughs. “And she invited Georgie. And I had two uncles, I used to call them ‘kid uncles’, ‘cause they weren’t much older than I was. They lived with my grandmother and grandfather, and they just lived around the corner from me in an apartment house. And we lived in a little two-family house. So my grandmother set me up. I went for dinner, and sure enough there was George, George Plausky at the time. When he and his brother went into the Army, his father changed their name, because he didn’t want to have a name that sounded Jewish. So they changed their name legally in New York to Powers. My maiden name was Gleberman. That’s also a very Jewish-sounding name.”

“Then what?” we ask.

Evelyn continues. “So my grandma had him up and we all had dinner. And he was going with a girl at that time, who he dumped the next week.” She throws her head back laughing, as if she had just given the punchline of the joke. “The minute he met me — it took me a little while — but for him it was love at first sight.” Evelyn laughs again and stands up.

"Let me take you through my house so you can get to know me. I don’t know why you’re interviewing me, girls.”

She passes by a photo of a young man on her wall, barely slowing down as she points it out to us. “This was my brother-in-law, who was the most gorgeous creature on Earth,” she says. “He was gay, and we always said, 'What a waste.’” Before the two of us have time to react, she has already moved on.

“My favorite picture — Well, I love Marilyn Monroe, so she’s in the house — but my favorite picture is Frank Sinatra. Here he is on the cover of Newsweek the day he died.” Evelyn’s walls are covered with Frank Sinatra the way many teens’ walls are covered with Justin Bieber. She is a 93-year-old fangirl.

“Evelyn, what do you like most about Frank Sinatra?” Hannah asks. Evelyn beams.

“Everything. He had the most wonderful voice. There will never be another singer like Sinatra. I’ve got hundreds of his albums, CDs, pictures, everything.“

Evelyn continues down the hall and leads us into her guest room. The floors are covered in the same pink carpet that’s in the living room. On each side of the room are two floral twin beds with an ironing board between them. Both beds have dolls neatly propped up side-by-side against the pillows. On the wall there is another picture of Marilyn, and more of Sinatra.

Evelyn does a sweeping motion with her hand. "This is the guest room. I haven’t had guests in a long time, but the ironing board always stays up. I’m an ironer. Just bring your ironing over while you’re here and I’ll do it.”

As we walk from room to room, it occurs to us that Evelyn’s house is, in many ways, just like Evelyn herself — colorful, sentimental, and full of character. I imagine that we could ask about any of her keepsakes, from a Raggedy Ann doll to an old teapot, and she’d be able to give us some kind of a story behind it. As she walks by a row of shelves stocked with dozens of knickknacks and figurines, Evelyn gives a playful sigh.

“I’m a collector. Look at this, it’s so ridiculous. They keep me company!”

“I used to collect dolls. These are my dolls, I have a million of them. They aren’t children’s dolls, they’re adult dolls, and their clothes are exquisite. I kept buying them because my husband never said no. I started collecting dolls when this lady came onto QVC. I’m a QVC nut. You asked about my lipstick earlier. I got that off of QVC also.”

Suddenly, Hannah is distracted by a framed photo of Evelyn’s face edited onto the body of a girl on the cover of Playboy magazine. “Just my face," she stresses. “They were doing it at some hotel in Las Vegas during a trip I took with George.”

George passed away ten years ago. They were married 58 years. Evelyn stares at a photo of her and George together for a long time. Hannah asks her what’s the secret to a long marriage, and Evelyn laughs quietly.

“What’s the secret? Keep your mouth shut.” She looks at us both intently.

“I had a husband who never raised his voice to me. He had the sweetest and nicest disposition. He never raised his voice in all the years we were married. Never. I have a very high-strung personality and he was very quiet and very calm. Took after his father. Had a lovely, lovely disposition. He was sweet as could be. And he was 91 when he died. But he had a very bad chest ‘cause he was stationed in the Aleutians while he was in the Army, and it was so cold there. It affected his chest so he always had a bad chest. Always had trouble with his chest. I think that’s what did him in, that chest of his.” She gives us a solemn look, a bit more dignified than sad, as if to say so it goes. She turns and continues looking at photos.

We try to picture Evelyn in New York as we know it now — the place where we go to school. We imagine it to be quite different now than it was back when it was Evelyn’s territory. Cailin asks how long it’s been since she’s been back.

“Would you believe I’ve only been back to New York once, years ago, since I’m living here. I never went back to where I used to live, because I used to live up in Westchester Country, on the border of, what’s that state right above us, Connecticut. I haven’t been back, but I hear that it’s changed a lot. I love New York. I miss New York. I’ve always missed New York. I loved the theater. We used to go to the theater when the theater was great, when they used to have some really good shows. Oh God, A Chorus Line, Mame, Gypsy. I love musicals. Beautiful music, Rogers and Hammerstein. Nobody writes music like that anymore.”

Hannah asks if this is true for all entertainment. “I think TV today is awful, too. Terrible. And I don’t even have a computer. I do still listen to the radio, though. 7 o’ clock every night I tune in.”

We ask if she ever feels like she’s missing anything. Her reply is quick, almost proud.

“Nope! What I don’t have, I don’t miss. I had a cell phone, which broke, and I never got another one. I don’t miss it.”

“And I drove up until a few months ago,” she says sternly. Even her pause is defiant. Suddenly, for the first time in our conversation, Evelyn’s face falls into an expression of sorrow.

She continues carefully. "I was in a little fender bender. It was really nothing. I mean, the front of the car was really smashed up, but it wasn’t my fault. I was driving very slowly. I don’t want to go into it, but my son — My son wouldn’t let me drive again after that. Took the car away from me.”

Of all the things we talked about with Evelyn that evening, she seemed most affected when telling us about her car. To her, we think, being able to drive was an important freedom.

Trying to cheer Evelyn up, we point out that she still seems to be keeping herself busy. She agrees. Cailin asks if that’s her secret to staying young.

“That, and luck and genes. I’m living longer than anybody in my family on either side. I’m mentally active. I did a crossword puzzle this morning and it was difficult. Maybe that’s my secret, crossword puzzles. I love to do them.“

As we make our way back to Evelyn’s living room, we suddenly want to know what she would say to each problem, no matter how small, that’s weighing on our minds. It occurs to us how rare it is to be able to hear wisdom from a woman with 93 years of experience, especially someone like Evelyn. But the sun is nearly down, and we know Grammy Ball is probably past expecting us home for dinner. We struggle to decide what we still want to hear from Evelyn before we say goodbye.

Cailin's last question for Evelyn is an important one: What advice would she give to the young generation, based on all of her own life experiences? Slowly and thoughtfully, she replies, "I would never change a thing. Just be careful who you’re with. What you talk about. Who you spend time with. You’ve got to be careful. You’ve gotta be choosy. It’s a crazy world today. You’ve got to be careful.”

We are nearly out the door when Evelyn stops us in our tracks. “Wait!” she says. “Come with me.” She takes us back to her bedroom and opens up her jewelry box. Inside is a collection of about a dozen beaded bracelets, each one a different color. She begins to choose a set of bracelets to match what each of us is wearing, and puts them on our wrists.

“You two are young, you should be wearing these while you can,” she says. “Take them.” Hannah tells Evelyn that she will think of her whenever she wears the bracelets.

“Stop that,” she says, in true Evelyn form. She smiles. We can’t believe we had spent all those years coming to that neighborhood, without knowing that we passed by the most colorful lady in Wilmington each time we went on a walk. We are imagining all our future visits to North Carolina to include a catch-up on Evelyn’s floral blue couch. We're both already looking forward to it.

It was right in that moment that we remember the peach tart. “I forgot to ask,” Cailin calls back to Evelyn as we head out the door. “Would you like us to bring you a slice of peach tart?”

Without hesitating, Evelyn looks us directly in the eyes.

“Okay, that I want. No, seriously.”