“I just never thought that was possible, you know, to make that kind of connection with these animals. So that’s kind of where I started with it. I felt like if I could get to that place, figure out what the animal was about, then I might be able to make a better photograph of it.”

VINCENT J. MUSI

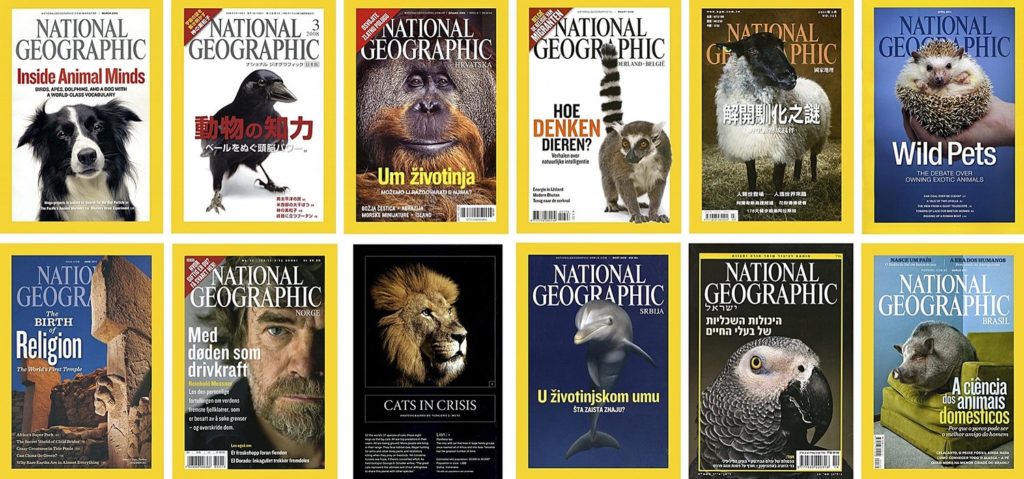

Vincent Musi calls himself “one of the most unlikely people to be photographing animals for National Geographic”—and yet, for over 10 years, that’s exactly what he’s made a living doing. We spoke with Vincent by phone about the assignment that changed the the way he saw animals—and his career path.

Hannah: You gave a TEDx Talk a few years back, and in that talk you said that your career started with you taking photos where the wild things aren’t. You didn’t start photographing animals until National Geographic assigned you a story on animal cognition in 2007. At first, you said, the animals wouldn’t look at you, and only made eye contact with the camera after you started talking to them. How do you talk to these animals to get them to cooperate with you? Is it just like you’d talk to another person, or different somehow?

Vince Musi: My initial approach was to deal with them like people—which, in the world of science, is not the best thing to do—to sort of anthropomorphize animals. But, I don’t care about that. I’m trying to make pictures of things that you’re going to care about, and in order to do that, I’ve got to make a cool picture of an animal that may be very famous, but not often photographed. Or at least in the way that I was trying to do it. So I was pulling out all the stops, because I was surrounded by, you know, sort of my heroes of photography, and they specialized in this sort of thing. I’m kind of like, I don’t do that. You know, I’m kind of a scrapper. I lied to get my job kinda thing. So I thought, well, I’ll do whatever I gotta do to do it. I thought, well, I’ll talk to ‘em, and I’ll talk to ‘em like they’re people. I’ll tell ‘em what I’m doing, and—you know, I think the tone of your voice is really important with some of these animals. Sometimes that worked, sometimes it didn’t.

In the case of the prairie dog you saw in there [the TEDx Talk], I tried everything. I shouted at him, I sang to him, and I kind of hit some chord, some note with him. He really did just absolutely stop fighting back and just listen to me, and we made some kind of bond kinda connection. I mean, I left there holding this prairie dog that for four hours wanted nothing to do with me. By the end of it, we were really good friends. I just never thought that was possible, you know, to make that kind of connection with these animals. So that’s kind of where I started with it. I felt like if I could get to that place, figure out what the animal was about, then I might be able to make a better photograph of it.

Cailin: Do you feel like you were born with this unique gift of, as you say, connecting with animals in a way that allows you to share them so well, or do you have a skill that you’ve perfected with time and practice?

VM: You know, I never really think about it in those terms. I mean, my father knew everybody in the little town we lived in outside of Pittsburgh. I thought he might be a politician—I didn’t really know what he did. My dad worked in a steel mill, but he seemed to know everybody. Waved to ‘em, couldn’t get down the street, wave left, wave right. He’s always sort of a friend, and always very courteous and outgoing, and honestly interested in what other people did. I have that. I’m really fascinated in what you guys do…and, you know, some of my inspirations come from the UPS driver that comes to my house everyday with stuff. It’s not always somebody that I’ve been sent to photograph. I’m naturally curious, and so I’m naturally curious about these animals. Those little things—that bond that you have with an animal if it’s your pet, that you know, but not everyone else gets. I have a very short period of time to kinda break through and connect in that way, and try to make a cool picture. That’s the challenge.

C: I mean, I’ve even seen a stunning studio portrait you’ve taken of a bee. How do you capture such a tiny, common creature like that so beautifully?

VM: You know, on that one I went to a guy who specializes in very tiny critters, a guy named David Liittschwager. He connected me with a guy at UC Davis in California, and that was one on the places where Richard Avedon made those stunning portraits in the 80’s of the guys with the bees all over them. Like how do you do…So I learned about bees the best that I could, and I found out it was really not that difficult—you know, the conditions—if you make it be a little bit cooler, they slow down a little bit. Now, the guy that was trying to help me with that bee picture kept giving them honey. At that magnification, it just looked terrible—it looked like it’d just come through a car wash! You know, ‘cause they have beautiful fur and all this cool stuff, and when you glop what seems to be like a pinhead sized drop of honey, it looks terrible. So I like to say that no bees were harmed during the making of those photographs, which was indeed true! We just put ‘em down for a minute, they kinda wake up, and they’re gone. Go get me another bee out of the cooler! [all laugh]

H: When you are going through photos after a shoot, and you have, say, 30 pictures of the same bee or the same hedgehog, how do you decide which one ends up in National Geographic?

C: Or is that not even your decision?

VM: Well, it is a little bit. So the hedgehog that we did that was on the cover [of National Geographic], we shot a series of hedgehogs for two days, and we probably shot thousands of photographs. You know, ‘cause I’m constantly changing the light, and you’re always at the mercy of an animal. You can’t make it do anything. I mean, you can try, but it’s kind of not the smartest thing to do. I always tell people it’s not worth stressing out an animal just for a photograph. So if it takes two days, we’re gonna take two, or three, or whatever. As long as nobody’s upset, particularly the animal. So we’ll shoot thousands of pictures, and in that case, as in the most cases, I work with one editor at National Geographic—it’s somebody I’ve worked with for a long time, her name is Kathy Moran. She does all of the stories on natural history, and she was the one who first offered me the assignment on animal cognition. So we work together pretty well. By the end of a story we could finish each other’s sentences even when we’re not in the same room. I’ll send every picture I take. So on the average story that could be ten, twenty thousand pictures. She’ll look through every one of them, I’ll look through every one of them, and we’ll come up with maybe 20-50 to show to the editor. It’s not a huge percentage. So in the case of the hedgehog, we might get it down to 100, and then get it down to 20, get it down to one, together. And then we’ll show that to the grown-ups and see what they think. So it’s not an individual decision, but at the end of the day, the editor-in-chief of the magazine makes that decision on what we’re gonna do. But we work very collaboratively. It’s one of the few places in the editorial world where photographers really do have a great say in how things are presented. They’re often the experts in whatever story they do by the end of the story.

C: I’m sure a lot of people wonder—I mean, I know so many people who are super into wildlife photography—and National Geographic is really like the ultimate goal for a lot of aspiring photographers. How did you end up with the publication?

VM: Well, I’m not kidding, I kind of lied my way into it. I had been a newspaper photographer on and off for about 13 years, and somewhere around 1992 the paper I worked for went out of business. I had always wanted to work for National Geographic, and so I went down there and went the normal route. And this is often the path for people: you work at a newspaper, it’s a training ground, and that’s a step into the door there. No one really starts their career out of Geographic. They’ve all come from some other place. And I like to tell people there’s no booth at the job fair for this position.

H: Right.

VM: And there’s really not much of a position anymore anyway. It’s really hard to do it. One of the paths back then in the 90’s was to go and do small stories, or help with a story. In my case I worked on a couple of book projects that were like driving guides in New England and stuff. Not very challenging, but it was work, and I had a bag of film and cameras and I was off in a Chevy Suburban for a month. The director of photography had been trying to get a story from him for a long time. And he called me on phone—I was on a pay phone in like Providence, Rhode Island—and he said, “I have a story. I need a short one-week’s coverage of a winter in the Shenandoah River. And I think you should do it.” It would be one week’s worth of work, it was gonna snow, and I need you to get from Rhode Island to Virginia. And I said no. And he said, “What do you mean? You’ve been trying to get this job.” And I said I’m not doing it unless I get the whole story, which was a far greater commitment, and one he was not ready to make with me. He said, “You don’t have the chops for that.” I said I want the whole story or i’m not going down there. He said, “What do you know about landscape photography?” I said I think about it all the time. It’s all I think about, landscape. It was a total fabrication! I didn’t know anything about what I was doing. He bought it, and next thing I knew I was heading to the Shenandoah River, where I would spend on and off the next year photographing a story on the Shenandoah River. It was my first published story in like 1998 for Geographic.

H: Wow. Fake it ‘til you make it, right? [laughs]

VM: Basically. And I never shy away from that, ‘cause don’t want anyone to think, Oh, that’s how he did it… I was never blessed with it. You know, a lot of guys, they’re the best of the best of the best, and I’m just simply not one of those guys. But I am fascinated by stuff, and I’ve been lucky enough to have a career over 30 years being a photographer, and getting to do that. It’s truly quite a gift.

C: Have you seen the industry change over the past 30 years since you started working in photography? ‘Cause now, you could be not just a photographer for a magazine or a newspaper or something like that, you can work on an app, you can work on social media, you can work on a website. How do you feel that the industry has changed in that way?

VM: There’s never been a greater opportunity to get published, but there’s never been less of an opportunity to earn a living at it. That’s the real challenge. The one thing that separates Geographic photographers, in my mind, from everyone else that’s out there—and there’s a lot of really great photographers in the world, maybe more than ever—but the Geographic photographers are like that Sylvester Stallone movie where the guys fly in there and try to rescue somebody from Kazakhstan. They’re The Expendables. You need somebody to go do that for penguins in Antarctica, you’re going to hire Paul Nicklen to do that, or one of these guys that isn’t gonna come back and say, “Hey, it was cold, it was rainy, the boat sank, we didn’t see any—” Like, we don’t have those options. They don’t publish excuses. So no one goes on assignment thinking it’s gonna be great—it’s actually horrible for the most part. The conditions are terrible. You’re often trying to make these fantastic pictures that are gonna be—people are gonna save these magazines, right? They never throw them away. It’s almost illegal to throw a Geographic away. So you’re terrified that you’re gonna fail. You figure, This is it, they’ve caught onto me. This is the last assignment I’ll ever get. You go through that all the time, on every one of these stories. But then what happens is you come back, and you do have this incredible body of work, ‘cause you have the time to do it, and the patience to make it work. That’s when you go, Oh yeah. Yeah, I went to Antarctica, and I did penguins. It was fantastic. It’s the thrill of my life! The truth is, you know, you’re dealing with—we have guys who’ve had frostbite like 26 times, and have these horrible infections like leishmaniasis—things that will potentially plague them for the rest of their lives. It can be really horrible, some of the things that happen to you on assignment. It’s not always a pleasure trip. It never is! I mean, in my case, I’m always in a lousy hotel room with a great view of the parking lot.

H: I know a lot of times when I’m taking my amateur pictures on my phone, I get frustrated because what I’m seeing through my eyes is, for whatever reason, not the same thing I end up seeing on my camera roll. Do you ever struggle with this? Like, maybe you’re shooting an animal with really wise eyes, or a unique demeanor, and find that they just don’t translate well through your lens?

VM: Always. I mean that’s the thing, it’s kinda like playing an instrument, right? You know, you may be the greatest guitarist in the world, and you’re still gonna play scales every day to practice. People say, “Hey, what kinda camera do you use?” I go, Why? Why do you wanna know that? What’s the difference? ‘Cause it’s not important what kind of camera it is. Every day for like 38 years I’ve picked up a camera and done the scales. I make photographs pretty much every day of my life. That’s what I do—try to get that thing to do what I want it to do, to say what I want it to say. And so, even at this point, I know a lot, but I still get frustrated, I still flip out. My wife is an incredibly far more important photographer than I am, and she’s been helping me with these portraits of dogs lately. It’s like, I’m just sitting there curled up in a ball on the floor going, “I’ve got nothing, I’ve got nothing, I’ve got nothing!” [laughs]

H: [laughs] And yet, you do, eventually!

VM: You know, you only see the good ones, right? You only see the ones that I like.

H: That’s true.

VM: Particularly when you’re on assignment for Geographic, the level is just so different in terms of the expectations of the editors, and the longevity of a photograph. You know, they last a long time, and we treat them like our children, these pictures. People really go kinda sideways over the fate of an image in National Geographic. Historically, fighting for a picture they really cared about that may not make the cut into the book. You really get attached to them in the end, particularly when there’s like ten of them, out of ten thousand. [laughs] And all these stories you see in there, you have to realize they can represent almost a year of a photographer’s life, sometimes more. It may be a short little feature, but from research and planning and field time and editing and proofing and all that kind of stuff, from start to finish, it’s a year. You get paid for a year, but you are spending a year of your life or more focused on one thing.

C: Yeah. You’ve gotta love the work!

VM: Yeah, you’ve gotta love the things. I’m surrounded by people who, now because of the sort of great potential for photography that you spoke of a minute ago, they’re becoming brands bigger than photography ever was. They’re out saving the oceans, and sharks, and documenting global warming on a scale that’s bigger than life. Paul Nicklen has four million people who follow his feed on Instagram. We have folks like Robert Clark who is desperately trying to document evolution, and in a very scientific kind of way. He’s done a great book on it. Everybody kind of breaks down into things they care about most, and have run with it with the power they never had before.

C: You call yourself “a trusted friend to animals everywhere.” [Vince laughs] Do you consider yourself to be an advocate for animals? Is there anything in particular thing you want to say about each animal you shoot, or animals in general, through your photography?

VM: You know, I think the thing I’m working on with dogs now…I know there’s something there. Right? And I can’t scientifically prove it. I’ve been around a lot of really smart animals that can understand language, and some that could speak. I was with a bird once that could count. I’ve seen lots of extraordinary things. A bonobo, Kanzi—amazing language abilities that bonobos have. So I know there’s something in there. And I always say that the more we learn about these animals, the more we’re learning about ourselves, and how they’re teaching us. On a very small level, this dog thing that I’m doing, is a little bit about that. I’ve been kind of forced to go back and identify breeds and stuff, but initially, I wanted you to just know their names. I would never say, you know, “This is Cailin and Hannah and they’re from… a place.” I would never describe you in that way. I would say what you do, and who you are. I feel that way about an animal. In this project I’m doing, I really want these dogs to not be greyhounds and great danes—I want them to be majestic, real cool animals that were shy, or boisterous, or fast. My interaction with them. If you are compelled to look at them differently in that way, no funny hats or collars and stuff like that, then I think I’ve been successful. I gotta tell ya, I’ve been overwhelmed with the response to it in just a short while. It’s really been amazing. [laughs] I keep saying, “Hope you like dogs, ‘cause that’s what you’re getting!”

I enjoyed this article almost as much as I enjoy your work Vincent!

Thanks so much for reading, Dianne! 🙂

Great article. Very talented photographer. Having personally known “Speedbump” the prairie dog pictured, I have to admit Vincent does make a connection with his subjects. He was actually cuddling a prairie dog!

Aww, this is so sweet to hear. Vincent really does seem like an amazing person. And we love Speedbump, even though we never met him! 😉 Haha! Thanks, MJ!! H and C

Great article. Very talented photographer. He was actually cuddling a prairie dog!

Hannah and Cailin Loesch, thanks a lot for the article post.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

Loved it! Fun interview!

Thanks so much, Alex! We are really glad you enjoyed it!

Hannah and Cailin Loesch, thanks so much for the post.Really thank you! Great.